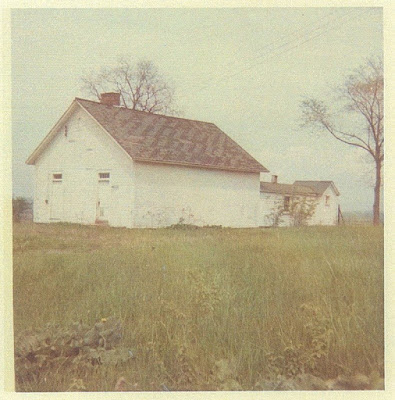

Young School after its closure in1960

Photo credit Christy Alger

Many generations received their primary education in one-room schools. One of the first actions in a new township was to designate school districts for rural neighborhoods. Usually a landowner/farmer donated an acre or so of land for the purpose, space enough for the building, the privies, and a play yard. Often the school teacher wasn't much older than her oldest pupils; teachers were most often single women, perhaps still in their mid-teens, the only requirement seemingly an 8th grade education and a willingness to teach. When a woman married, that was the end of her teaching career!

If she remained single, she might be labeled as a 'school-marm.'

In the era of limited travel teacher boarded with a local family, either one who had children in school or an older couple with a 'spare' bedroom.

My sister Christy recently became involved in a hometown project, the brain child of several people working with the local library and historical society [housed for more than a century in the same elegant and venerable building on the main street of Orwell, Vermont.]

The plan was to interview or otherwise collect the memories of the increasingly few individuals whose early education took place in three one-room schools that remained open during the 1950's before all were closed and students bussed to the 'Village School.'

Knowing of my interest in history and my penchant for writing, Christy passed the assignment on to me.

I began with a search using my subscription to newspapers.com, an affiliate of ancestry.com.

I was able to collect news notes from local papers spanning 1920-1960 [Young School closed its doors after the 1959-1960 school term] and created a chronological review before starting on the composition of a personal memoir of my own school years.

I've decided to post the memoir in several installments; that way I'll have it accessible for as long as blogger and I are around.

Nostalgic essays aren't everyone's favorite reading, so you are fore-warned!

Sharon, Christy, Margaret, circa 1953

I remember that dress--a yellow and brown print with a peplum and brown piping trim.

Looking Back: School Days

Part One

The one room white-painted schoolhouse faced west onto Young Road, fronted by a rutted wing of gravel that gave way to wiry well-trodden grass. A transomed door accessed by shallow cement steps, led into the entry, a matching door opened to the coal bin, A long divided ell connected the back of the main building with two attached privies, one for the boys, one for the girls. Fences on the north and east separated the schoolyard from the Stacy farm's pastures. A hedgerow of trees at the north boundary cast shade over the back windows of the building in spring and fall.

The unheated entry had rows of hooks on the left wall for jackets and caps; on the right wall were shelves to hold students' lunch boxes and the heavy blue-striped crock with a spigot for dispensing drinking water; each day two of the older boys would carry between them a water pail filled at the Stacy milk house.

Stepping inside, across from the door was a bank of tall windows which covered about 2/3rds of the east wall. Blackboards were mounted on much of the right hand wall, with a low table and small chairs arranged there for hearing the youngest children's reading classes. A closed cupboard to the right of the doorway held various supplies of paper, boxes of powdered 'poster paint,' paste jars, extra pencils.

I don't recall my official first day of school in September, 1950. I'm thinking that for at least the first week Mother would have driven me the ½ mile up the road to the white clap-boarded building, maybe even collected me in the afternoon.

A fragment of memory persists of a late afternoon during the previous year when my hand firmly in Daddy's grip, we walked up the dirt road and Daddy pointed out the school I would soon be attending.

The schoolhouse door was open and when we stepped quietly into the entry we discovered that the teacher, Miss Ruth Goddard, was there as was Phyllis Stacy who lived next door.

In my mind the sense of autumn persists: warm afternoon sun, goldenrod blooming in the rough verges of the road. The walk home after my father had exchanged a few pleasantries with Miss Goddard is not in the picture.

During May, 1950 Young School held a 'visiting day' for children who would enter first grade in September. Mother arranged with Iris Stacy that I would go home to lunch with Phyllis, then in 4h or 5th grade. At the Stacy home I was shown to the bathroom, then served a light meal in the Stacy's pleasant kitchen, after which I followed Phyllis up the slope, through her grandparents' yard and so back to school. There would be several other children in my first grade class; were they present on that day? Did Miss Goddard give us crayons and paper? How did we spend the hours?

As the new school year got underway I walked the half mile most days, trudging behind an older girl, Betty O'Brien. Betty was a stolid person, taciturn and studious, probably not impressed with having a first grader tagging behind. Conversation with her was not encouraged.

The next year my younger sister Christy started school and there were other neighborhood children straggling up the road, singly or in family groups: Downeys, Labsheres,and then later the two Quenneville girls, Simone and Jane.

The teacher for the first four years that I attended the Young School was Mrs. Viola Disorda of Sudbury, the next small town to the east. Mrs. Disorda, a seasoned area teacher, was age 45 in 1950. She was a buxom woman with lavender-grey hair that curled about her face. She wore crisp dresses, neat cardigans, a brooch at her collar, colorful earrings. She used a peachy face powder, a hint of rouge and red lipstick.

One of the most memorable things about Mrs. Disorda was her musical ability. There was no piano at the Young School, but within weeks of Mrs. Disorda's installation she must have put out a plea for an instrument.

In what was referred to as 'the old house' across from my Grampa Mac's farmhouse, long since used as a storage space, there was a parlor pump organ. This was offered to the school, conveyed there, dusted off and put into immediate use. Mrs. Disorda played well with a lively beat. [I learned much later that she was in local demand as a 'rag-time' pianist.] Mrs. Disorda didn't drive and was conveyed to and from school by her husband, Alfred Disorda, a wiry rusty-haired man who drove an ancient pickup truck. On winter days, Alfred came in to deal with the coal stove before going on his way.

The songs with which we opened the morning session [after the flag salute] were standards from the Golden Book of Songs: patriotic numbers such as 'America the Beautiful,' 'Tramp, Tramp, Tramp,' old sing-along favorites such as 'Red River Valley' and 'Clementine.'. How did we learn them? Were the words written on the blackboard? Memorized by rote? I could learn words and melodies quickly and found these 'morning exercises' to be the best part of the school day.

During the tenure of Mrs. Disorda the school accommodated 8 grades. The great hurdle for first graders was learning to read. I had an advantage in already recognizing and being able to print the alphabet. We were drilled on simple words by the use of 'flash cards' and then began the adventure of putting those words together in the very simple tales of 'Dick, Jane, Sally, their dog, Spot, their cat, Puff.' [Look, look, see Spot run!] With reading class over we turned to workbooks featuring exercises such as circling the non-matching object in a pictured group. As a way of stressing the alphabet we were handed a big sheet of paper, a folded paper towel with a gob of paste, and directed to cut pictures from a stash of old magazines and catalogs—the idea being to identify the letter of the day and paste our examples onto the paper. We applied the glue with our fingers and there were those who found the sticky residue tasty. Learning to write was accomplished by at first tracing and then copying upper and lower case letters on specially lined yellow paper.

Photo credits Christy Alger

I was quiet with a studious nature and as my difficulties with math comprehension were yet to be revealed I could complete my work quickly and neatly. Learning to read and write opened a world of exploration and adventure.

Many of the students belonged to a large French Canadian family who didn't speak English at home. For these children first grade was a struggle of learning to comprehend English, a process which meant that each in turn repeated the first grade to get on with the rudiments of using a language that was foreign to them.

Disturbances

The first weeks of school were a delight. Girls in the upper grades were kind to the younger children and I became friends with two girls a grade ahead of me. If my remembered count is accurate there were 23 students in attendance in the 1950-51 school year ranging from first through eighth grade. Eight of those pupils were from the French Canadian family, four were from a sizable family lodged in the Quenneville tenement house.

From these two families there were six boys who began to 'sass' the teacher, or create distracting noise and disruptions. My desk with the other primary children was in the front row and I seldom saw what started the disturbances which quickly escalated to full-on battles between the boys in question and Mrs. Disorda. When reprimanded they refused to obey, 'talked back,' grumbled. On such occasions Mrs. Disorda might approach the culprit with a ruler or blackboard 'pointer' in hand, her voice raised in scolding. During one fracus she snatched up the stove poker and brandished it. After such confrontations she sometimes retreated to her desk at the front of the room, angry tears streaking through her face powder as she attempted to compose herself before continuing with the next class recitations.

One chilly morning after a day of more than the usual series of disruptions, Alfred Disorda waited inside the school room for the older boys to arrive. Taking a stand beside his wife he lectured the boys on their disrespectful behavior. Alfred was a man of small physical stature with little command of words, but he was plainly indignant. After he left the boys shuffled, smirked, swaggered to their seats, unrepentant.

These altercations had a frightening effect on me and so I began a spell of fussing that I didn't want to go to school. I wasn't able to articulate to my parents why the tense atmosphere was spoiling school for me. What I could do was to balk, wail, sit solidly on the floor and protest that I no longer wanted to get ready for school and out the door of a morning. My mother's distress was great and her patience with me was laudable. In the end, each day after my stint of unhappy rebellion my tears were mopped up, my face washed and I was delivered to the school house door. I don't recall how long I continued to stage my miserable protests; in the end, I understood I was expected to attend school and make the best of it. I may have eventually realized that the unpleasantness wasn't a daily occurrence, no one was likely to be physically harmed, and I couldn't waste each day in dreading what might happen.

It is interesting to look back and realize the combative boys ranged in ages from 8 to 12. Three of them were from the French-speaking household. While they had learned to communicate in English most of the school subjects involved reading and writing, likely still a challenge. Their home situation was turbulent, they carried responsibility for many chores; sitting at a desk with a book opened before them likely had little appeal. The remaining three boys seemed alternately surly or mouthy. Neither of the families would have been approachable to discuss behavior problems if the teacher had even wanted to admit that she wasn't in control of her classroom.

No comments:

Post a Comment