Friday, May 30, 2025

End of May

Sunday, May 25, 2025

Weather and Gardens

Wednesday, May 14, 2025

School Days; A Memoir; Final Installment

Students who were following the 'college course' expecting to continue education after high school graduation or chose instead a 'commercial course' had to travel out of town to one of the area 4 year high schools. My mother, Beulah Lewis Desjadon, had graduated from Brandon High School as Salutatorian and went from there to the two year teachers' training course then offered at Castleton Normal School [later Castleton College.] It was her hope and expectation that I would also prepare for a teaching career. By this time I had misgivings as to my suitability for teaching, but the college prep course offered the best options.

In earlier decades young people studying out of town had to board within walking distance of the high school of their choice, an added expense for parents. By the late 1950's and early 1960's the option was to find a ride to Brandon with an older student whose family had provided their recently licensed offspring with a car, or as happened for my sister and me, the opportunity to wait on the corner of Young RD and Rte 73 for a teacher who taught in the Brandon Elementary School.

In Brandon we were let out at the foot of the hill to trudge, book bags slapping at our hips, up the street to the three story brick building which was little changed since my Mother's school days.

The adjustment required for this transition wasn't as surprising as the earlier one although there was now the challenge of a different instructor for each class, bells ringing to signal the ending of a session, the march up and down stairs to the next classroom. Student traffic was marshaled in one direction: one's next scheduled class might be in the adjoining room, but to avoid traffic jams one merged with the throng thumping through halls and crowded staircases wheeling off when the designated room came in sight.

I was again in band—a marching band this time—and in chorus. My best friend from home, Linda, was there and I made casual friends among some of the other quiet girls, most of whom had come in from the outlying smaller towns.

The schedule was grueling; we had to be at the corner to catch our ride at 7:30, arriving home after 4 p.m. Supper, homework, bedtime and trying to fall asleep before midnight in preparation for doing it 5 days per week.

In 1961 Brandon High School joined the newly created Otter Valley Union District; Orwell assigned its students to Fair Haven Union High School. My senior year was spent there, my 4th school although I had never moved from home.

I was weary of school. The past two years of high school with the early morning commute, the long hours, had worn me down physically. I had ordered a few college catalogs, although I now recognized that college tuition would place a heavy strain on my parents. My pitiful scores in Algebra I and Plane Geometry had kept me from the Honor Roll so in spite of my high scores in subjects that required proficiency in reading and writing I was no candidate for a scholarship. I had also realized that I was not teacher material. I leaned toward the idea of becoming a librarian, but was surprised to learn that unlike the women who had served in that position in our small towns, to be considered for the job at any paying level required a college degree.

So, I was without plans for any scholastic future.

When I signed up for senior classes at Fair Haven I found I already had finished all the requirements to graduate there other than English IV. A schedule was made up for me: English IV; Latin II; Home Ec; Personal Typing, Speed Reading; Geography. Several of these classes were mainly populated by Juniors and Sophomores. The young man I would later marry sat in Geography class, as did my younger sister.

Fair Haven is a border town as are several of the towns in the union district. Many of the area students' grandparents and parents were Welsh, a few were Polish, families who had come to the US to work in the slate and marble quarries. It was a more 'blue collar' background with friendships and associations more recently formed. I knew most of the students on the high school bus, made connections with others who likewise were bussed in from surrounding towns.

I wasn't unhappy there but it felt like a rather plodding final year.

A few incidents stand out in memory. One happened as a result of English IV.

The teacher, Mrs. Margaret Onion, treated us [we were told] as we could expect to be treated if we went on to college. She was formidable! We read Beowulf, Canterbury Tales, Macbeth. We also took on Pygmalion which had been popularized as My Fair Lady.

Pygmalion was read aloud in class with the parts assigned on the spot. Mrs Onion called on me to read the part of the waifish and inelegant Eliza Doolittle.

I was horrified, the 'new girl' in class! After a moment of near panic I decided that if I must be Eliza I would do it with flair! I still have a recalled sense of satisfaction that I, the quiet little mouse, portrayed Eliza in a way that caught the attention of both teacher and classmates. As class dispersed at the sound of the bell, a girl I knew only by name approached me offering an invitation to join the Drama Club.

After school 'extra activities' would have meant catching the 'late bus' home. It would have meant endless rehearsal time. It would have meant eventual public performances something I couldn't have faced at that time.

I didn't volunteer to be a pianist for the chorus group rehearsals; a good friend from Orwell suggested it when the music instructor rose from the piano stating in frustration that she couldn't both direct effectively and play accompaniments. I was excused from other classes on music days to pound out tenor or alto parts for a learning session. I took home music scores so I could learn the more difficult piano accompaniments. I prayed for the good health of the girl who was the usual pianist for school concerts.

I graduated, not with honors due to my lack of proficiency in math, but placed respectably in the top third of the group.

I worked a summer job as I had since I was 16. Another job in a small local business saw me through the winter and spring. My Mother warned that I needed further education, 'something to fall back on' as she put it. Academically, in spite of my aversion to math, I was qualified to attend college. In terms of physical stamina and emotional maturity and discernment I suspect I would have been adrift in the college environment of the 1960's.

The subject background and the study habits I formed during elementary and high school have served me well. I am still often 'lost in a book' or in research of those subjects that interest me.

I'm still at my best and most comfortable in a small group of friends, family and acquaintances who enjoy the sharing of ideas, interests and knowledge.

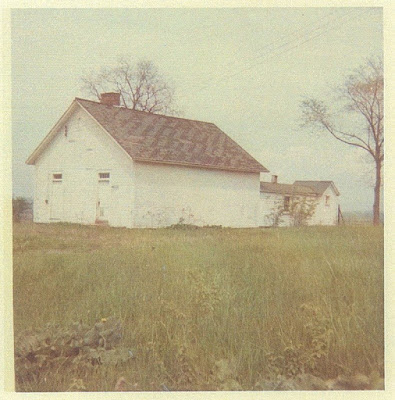

School Days; A Memoir, Part Three

The teacher of a one-room school had to be versatile. There might be half a dozen or more children in one grade, only one or two in another; if some children had repeated or skipped a grade there might be no children in a particular class. All the classes and recitations had to be accommodated within a small space. The teacher not only needed to instruct in the basic learning skills but was expected to present something that resembled an 'art' class several times per month. Here the stash of Grade Teacher magazines came into play.

'Art class' usually consisted of a seasonal drawing traced from the magazine pages and handed out to all along with colored pencils and crayons. The magazine example was tacked up in full view and the idea was to replicate it. Originality wasn't encouraged. I learned this in 4th grade when the Friday afternoon subject was a basket filled with flowers. The example was a blue basket. I was familiar with the vintage baskets, homely brown, in use in my grandfather's house. That is how I colored my basket. When she collected the pictures which would be pinned to the bulletin board, Mrs, Disorda held my masterpiece at arm's length and scolded, 'Who would want an old brown basket? Couldn't you see that it was blue?'

During Mrs. Gray's tenure Mrs. Harriet Cushman came to teach art. The project I remember best was more 'craft' than art—we were earlier instructed to bring a small bowl from home. We then happily and messily tore strips of newspaper, dunked them in a basin of sloppy paste and formed the strips in layers around our bowls. These objects were set aside to dry until the next session when the hardened shells were gently tapped loose. I was pleased to see that my papier mache bowl was well shaped and sat firmly on its bottom. I blended a custom color from the poster paints, mixing brown and orange to create terra cotta. I embellished the painted bowl with a band of white surmounted by free-hand cat faces. I huffed to Mrs Gray when I discovered that several people 'copied' [clumsily I thought] my choice of color and decoration. She listened patiently, acknowledged my frustration and quietly replied, 'When someone copies what you've done, try to consider it a compliment. It means they like your work.' The little bowl sat on my bedroom shelf for a long time holding a collection of small oddments.

Mrs. Fairie Tyler Atwood taught music in the local schools for several years. She was a lovely young woman, slender with strawberry-blonde hair. I was familiar with her as she sometimes played the pipe organ at church or performed vocal solos. She also gave private piano instruction; Mother had taught me to read music and encouraged me through the first book of lessons before deciding I would benefit from further study with Mrs. Atwood. I looked forward to the afternoons when she would arrive at the Young School and yet I have little memory of her presentations. The most enjoyable times were when she was leading us through The Virginia Reel. Having explained something of the history of this frolicsome dance, she lined us up in facing rows to learn the steps while she played a lively tune on the violin.

Book Mobile

A wikipedia article states that bookmobiles were at the height of their popularity in mid-20th century.

The bookmobile that turned up several times per year in the driveway at Young School was a van fitted with shelves. It was driven by Miss Ball, a plain-faced woman with an engagingly toothy smile. She dressed for whatever she might encounter in the way of muddy or rutted dirt roads, wearing a sensible plain skirt or trousers, a tweed topcoat, with a red beret confining her short greying hair.

After making sure that our shoes were relatively free of mud we were allowed by grades into the tight space of the van. I think there was a limit on how many books each student could select. I loved to read, was happily working my way through the selections in the children's room of the town library. I chose books considered above my grade level and hoped that others would be selecting books that I would enjoy.

The classroom rule was that if assigned work was finished before the next class was called to recite or hand in papers, we could go to the bookshelves and choose a book. There was a sparse collection of books owned by the school and these were always available. By 4th grade I had read them several times over so was glad of additions from the book mobile. I remember a book of Greek and Roman Myths, several volumes of fairy tales suitable for inducing nightmares; a favorite was the story of a family who converted a one-room schoolhouse into a family dwelling.

Strangely, Mrs. Disorda sometimes scolded me for being 'lost in a book.'

Transitions

I don't recall anticipating the transfer to the Village School for 7th grade with any particular misgivings. The actuality was rather unsettling. After that first year at Young School when I had felt intimidated by discord created by the older boys, I had made my place in the small group setting and school terms meshed with my interests and activities outside of the school year.

I was acquainted from Sunday School with a number of children who were in my 7th and 8th grade classroom, but mere acquaintance didn't lead to automatic inclusion in the cliques that had been years in the making among the village kids. I was then----even as now----a quiet introvert without the striking looks or personality that enable one to burst into a group as a welcome addition. I was clumsily uninterested in athletics although I did later manage to join the squad of cheerleaders who cavorted about at the basketball games held in the old town hall.

During those early weeks in the new to me environment someone tagged me with the epithet 'stuck-up.' I still don't know why that characterization originated or how it gained any traction, but it did somewhat haunt my time at Orwell Village.

My interest in music provided a source of affirmation as I could sing in 'special' groups or duets for the Christmas and Spring concerts.

I played 2nd clarinet in the school band which was presided over by Mr. Richard Oxley. Mr. Oxley served as First Chair Trumpeter in the Vermont Symphony Orchestra and it was clear that our efforts often strained his patience. His personality seemed the epitome of artistic temperament. Repeated efforts at rehearsals to drill rhythm or pitch into the less musical of his band members left him wildly brandishing his baton, groping for a cigarette, running his fingers through already disordered hair. Invariably, on the evening of a school concert he imported two of his accomplished daughters, one with a French horn, the other with an already astonishing prowess as a trumpeter.

School Days; Part Two

Blogger displays the newest post on top, so if you've not read Part One of this saga, here is the link.

School opened at 8 A.M. with a break after about two hours for morning recess. Unless the weather was truly horrid this was the time to rush outdoors, shout, gallop about, take turns on the swing set; if we needed a drink of water or to visit the privy, this was the opportunity After 15 or so minutes teacher came out to the front steps and rang a hand bell to summon us inside. The hour and a half before noon was devoted to arithmetic classes. The upper grade students worked problems at the blackboard, there was written work to be completed and passed in. For the primary children there was learning to recognize numbers and eventually to learn simple addition and subtraction sometimes with visual aides to demonstrate the process.

There was a sense of relief when the hands of the big wall clock moved to 12 noon, books could be put away and lunch boxes brought out.

Lunches prepared early in the morning, held in a metal lunch box [or a lard pail or paper bag] were rather spartan. A sandwich curling in a wrapping of waxed paper, an apple or banana, a cookie. Milk, even with chocolate syrup added, tasted 'off' after several hours in a small thermos. I picked at my lunch not realizing there were children in the room whose lunches were so meager they would have enjoyed what I rejected.

With lunch over we had nearly 45 minutes left to be outdoors. The boys usually threw or kicked a ball. The older girls were good at organizing games for the younger children, London Bridge, jump rope, hop scotch. The whole school played Red Light, Green Light. In winter we tramped out a messy circle in the snow for Fox and Geese, or slid and slogged about, falling, wallowing in wet snow until we were red-cheeked and cold. Winter boots of the day were clumsy things pulled on over shoes; snow pants made of wool were thickly bulky and once saturated with melting snow took many hours to dry. Mittens became caked with snow, the fingers within chilled.

When the weather was too cold or wild to be outside we learned to square dance. The school owned a set of the Durlacher records ['Honah your Pahtnah'] desks were pushed back and we happily stomped our way through 'alle-mand right and left' and 'do-si-do.'

Afternoon classes began with a quiet time. With everyone back in their seats the teacher read a chapter from a storybook chosen to have appeal for both the older and younger children. Some put their heads down for a quick nap. [Heads on desks could also be commanded if the school room had gotten noisy or children weren't settling well.]

During the last 15 minutes of the school day the classroom was tidied. Books and papers were put away, chairs straightened. Children took turns to erase and wipe the chalkboards, the felt erasers were taken outside and 'clapped' to rid them of the day's accumulation of chalk dust. Two of the older boys had the privilege of bringing in and carefully folding the flag. The floor was swept, windows closed and fastened; in winter the coal fire was banked with a last hod of coal.

Hot Lunch Program

I was in 3rd or 4th grade when a free hot lunch program was provided for Young School. I expect this was at least partially government funded on a state or local level, though I recall a card party held in the cafeteria of the Village School as an effort to raise funds. The meals were prepared and brought in by a woman in the neighborhood whose pay for doing so was likely a mere stipend. Some of the food items were 'commodities,' other components would have required a trip to the nearest large grocery store. The meals were carb and calorie laden, hearty, plain and delicious, similar to what many of us would have been served at home. For the big families with meager means the hot lunch probably provided the best meal some children had for the day.

Laura O'Brian served as the first cook; in the following years Grace Christian took over the role of lunch lady. Laura worked a late shift at the local plywood veneer factory, had her own car. Grace's husband, Lambert, assisted her with packing in kettles and covered pans. Did he wait outside in the car or drive back the scant two miles to their home and then return?

While auburn-haired Laura was quietly efficient in serving food, Grace, a lanky, plain woman, had a loud and cheerful voice. The content of the lunches didn't vary greatly, but the savory smell of hot food being set out on the table at the front of the room made concentration difficult for the last few minutes of arithmetic class

There was a tray of sandwiches, peanut butter and jelly on white store bread; usually a large towel-shrouded kettle of mashed potato; thick gravy made from canned beef or pork [the commodities!] canned veg—corn, peas, green beans with an occasional substitution of canned applesauce. Dessert might be a square of frosted yellow or chocolate 'sheet cake.' Fridays were meatless—both cooks and many of the children were Catholics—with mac and cheese a standard offering. There must have been a few menu variations I don't remember—surely baked beans might have figured in a New England community, perhaps a pan of apple crisp made from the abundant local apples. Milk was served in half pint cartons to wash all this down.

I think we were required to bring at least our own silverware, possibly also an unbreakable plate for each person. There was never any question of each child paying for their lunch.

There was no running water at the school; I hope we lined up before lunch to whisk our grubby paws through a basin of cold water and dry off with a brown paper towel.

Programs and Parties

A Christmas program and Memorial Day 'exercises' were held each year. Both were anticipated events to which parents and neighbors were invited.

Preparation for the Christmas program began as soon as classes resumed after the four day Thanksgiving recess. Cut-outs of black Pilgrim hats and hectically crayoned turkeys came down from the bulletin board to be replaced through December with Santas, stars, Christmas trees and bells cut from red or green construction paper. The off-cuts of construction paper were sliced into ½ inch strips to be looped and pasted [that delicious paste!] into festive paper chains.

Teachers of the day subscribed to a magazine, 'The Grade Teacher,' and from their hoarded copies came the poems, skits and acrostics to be laboriously committed to memory. Rehearsals went on for days with children nearly frantic with anticipation during the last week before 'the program.' Someone's father would bring in a small hemlock or pine cut from a back pasture and an after lunch session was dedicated to trimming the tree with our construction paper chains, wobbly stars and a string or two of Christmas lights supplied by teacher.

One memorable year there was to be a skit in which the younger children were meant to be pajama clad [these to be pulled on over clothing] a sort of waiting for Santa presentation. One grubby little girl from the poorest family innocently confessed that she had no pajamas or nightgown as she went to bed in her slip. On the day before the program there was the quiet presentation of a new flannel nightgown for Patricia; on the night itself most of us turned out in suspiciously new and nappy flannels.

On the evening of the Christmas program parents, grandparents, younger siblings and neighbors crowded the over-heated schoolroom; those grownups who could fit appropriated our desks as seating, a few chairs were put into use, many of the dads leaned against the back wall. We sang our songs, popped out from behind the improvised bedsheet stage curtain to speak our pieces, teacher always just out of sight to prompt anyone suffering stage fright.

I was usually taught a vocal solo meant as a surprise for my mother. Since I could never keep a song to myself and would unwittingly sing it at home Mother had to feign surprise. After my debut performance while a first grader various grownups patted my head telling me I had sung beautifully. I recall that when the last exiting mom praised me saying, 'You sang good,' I wearily replied, 'Yes, I know I did!' [Insufferable little creature!] She immediately reported this to my Mother and on the way home I was given a lesson in the more appropriate response.

As the final song of the evening was belted out there was a great stamping and 'ho-ho-ing' from the entry—someone's dad or uncle had slipped out, squeezed into a red suit, pulled on a cotton batting beard and was prepared to hand out gifts from the tree. There would be tokens from the teacher [who would receive frilly handkerchiefs and jars of hand lotion or, from some child's talented mom perhaps a crocheted doily.] Children could expect colorful boxes of hard candy, popcorn, a nice small gift from the teacher. There was also the custom of 'drawing names' so that each child could give and receive a gift from another student. During the years of the large French family there was an unspoken feeling of dread, for if one of those children drew your name only the cheapest and most disappointing trinket could be expected.

The Memorial Day presentation was a more solemn occasion though no less preparation was made. Some fathers of students had fought in WWII, there had been family members lost to war. Memorial Day exercises were an afternoon program with most of the fathers away at a job or deeply involved in the push of spring work on the farms. Some of the women who attended brushed away tears as we recited our poems, declaimed the Gettysburg Address, waved our little flags and stamped our way through flag drills. We sang, “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory of the Coming of the Lord', voices rising jubilantly on the chorus, 'Glory, Glory, Hallelujah' while petals fell from the white lilacs we had cut that morning from the bushes that grew in the schoolyard.

For the program in my final year at Young School I memorized 'The Blue and The Grey' and for quite a few years after I could recite the entire poem; now only a few lines remain if memory is jogged.

“By the flow of the inland river,

Whence the fleets of iron have fled,

Where the blades of the grave-grass quiver,

Asleep are the ranks of the dead:”

We were fervent in our singing and marching and recitations, with no concept of the history of war behind us or yet any hint of what was to come.

Though never as elaborately prepared as the Christmas or Memorial Day programs we did observe Halloween and Valentine's Day with school parties. On the day, afternoon classes were suspended. We wore masks [Halloween] bobbed for apples [a messy and unsanitary game which I despised] ate great gobs of candy corn, chocolate, popcorn and apple cider. No one spoke in those days of excess sugar consumption and the behavioral or health issues associated; we went home for the weekend hyper and half sick.

Valentine's Day was a quieter afternoon, a crepe paper decorated box into which we had placed our cards, many homemade, the passing out of heart-shaped pastel candies inscribed with flowery sentiments.

Changes

I don't recall what year the Young School enrollment was reduced to six grades. During Mrs. Disorda's final year with us [my 4th grade] the 'big kids' had moved on, the unruly boys were gone. Several families contributed first graders nearly every year, there was little change in the surnames of the group.

When school opened for my 5th grade year, there was an unfamiliar teacher greeting us. Mrs. Lois Sullivan traveled from her home in Salisbury. This may have been a return to teaching after a hiatus of some years. . She didn't have prior acquaintance with our families, was just learning our names and personalities, establishing a routine when after several weeks she left us. I later learned that she had a household of husband and young children, was active in the family business and in town affairs. It would seem that she thought better of adding full time teaching to her life at that time.

We were surprised to return to school on the last Monday in September and find another new teacher already seated at the desk.

Mrs. Arlene Gray had served in the military as had her husband. They had been struggling to make a going concern of a lake property with a seasonal restaurant catering to the yachts that trawled along Lake Champlain.

Mrs. Gray conducted classes in a more relaxed and unstructured way than her predecessors. She was quietly firm and there were no discipline problems. Mrs Gray wasn't musical, but she read aloud well and the time formerly spent in singing was now a story time.

She dressed simply in twill skirts and plain blouses. For the Christmas Program or other formal meetings she appeared in a well-tailored dark suit that may have been a remnant of her military years.

That first autumn of Mrs. Gray's tenure coincided with a seeming explosion of the resident squirrels who scampered through the bare branches of the shag-bark hickories outside the schoolroom windows. Mrs. Gray encouraged us to notice the antics of the squirrels and to acquaint ourselves with the names and habits of the birds we could see. Her appreciation of the outdoors resulted in a December trek to a nearby neighbor's snowy woodlot where with his permission we selected the schoolhouse Christmas tree, carefully cut down by the older boys.

In May she led us along Knox Hill Road below the schoolhouse where a variety of wildflowers grow.

Fifth grade brought the introduction of fractions and my faulty grasp of math concepts began to emerge. After days of frustration—probably both for me and the teacher—Mrs. Gray had each of us cut a large circle from 'oak-tag' as a base. More circles were created from colored construction paper and we were shown how to use ruler and compass to mark each color into pie-shaped wedges representing halves, quarters, eights, thirds, sixes. Layering these 'slices' in different configurations I could begin to see the relationships. It probably resulted in the most comprehensive vision of math that I have retained.